How Well-Structured Feedback Causes Eustress And Impacts Employee Performance

This report examines how well-structured feedback – characterized by clarity, specificity, timeliness, and contextual relevance – can act as a challenge stressor that elicits eustress (positive, acute stress) in employees and how this, in turn, influences performance. It synthesizes insights from organizational behavior, psychology, education, and related fields, focusing on professional work settings

Well-Structured Feedback as a Positive Stressor

Feedback delivered clearly, specifically, and promptly tends to be perceived as a challenging but manageable demand rather than a threat. Such feedback reduces uncertainty and provides actionable direction, which can convert the stress of evaluation into eustress – a motivating force. High-quality feedback correlates with better productivity and performance outcomes compared to vague or delayed feedback.

Eustress vs. Distress

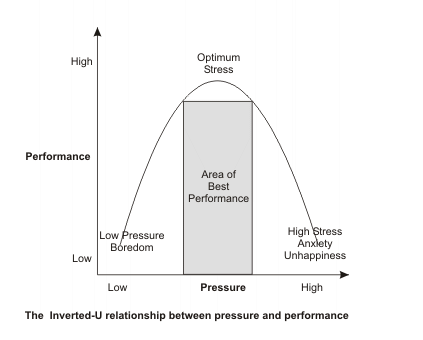

Eustress (the “good stress”) is a short-term, stimulating state that enhances focus, energy, and motivation, whereas distress is an excessive or negative stress that impairs concentration and decision-making . Research confirms an inverted-U relationship between stress and performance: moderate levels of acute stress can boost performance, but too little or too much stress undermines it[1]. Well-structured feedback often aims to hit that optimal zone by pushing employees just enough to spur growth without overwhelming them.

Cognitive Impacts

Eustress triggered by constructive feedback can sharpen an employee’s mental focus and improve cognitive functions like attention and problem-solving in the short term. Under manageable stress, individuals concentrate on pertinent cues and filter out distractions. This heightened focus and sense of urgency may lead to quicker decisions and creative problem-solving, provided the individual doesn’t interpret the situation as threatening. However, if feedback is delivered poorly (unclear or overly harsh), it can provoke distress, leading to tunnel vision, impaired judgment, and rigid thinking as employees fixate on fear or failure.

Performance Outcomes

When feedback-induced stress is appraised positively, it tends to increase engagement, motivation, and performance. Employees experience a surge of positive affect and self-efficacy, fueling better focus and persistence on tasks. Empirical studies show that challenge-type stressors (like constructive feedback or difficult goals) enhance productivity, learning, and even creativity, as seen in higher employee thriving and innovation under challenge stress[2]. Conversely, feedback that triggers threat appraisals can erode confidence and performance – for example, negative feedback delivered poorly can diminish subsequent performance and creativity due to increased anxiety or a defensive focus on avoiding mistakes.

Individual Differences

Not all employees respond to feedback stress in the same way. Personality traits, mindset, and coping styles critically moderate whether feedback creates eustress or distress. For instance, individuals with a growth mindset or a “stress-is-enhancing” outlook tend to view critical feedback as an opportunity to improve – they seek feedback, accept criticism, and respond with effort and resilience[3]. This appraisal leads to excitement and a challenge response (eustress) that boosts performance. In contrast, those with a fixed mindset or high neuroticism may perceive the same feedback as a personal threat, triggering negative emotions, avoidance coping, and performance decrements[3]. Self-esteem also plays a role: employees with lower self-esteem show heightened stress reactivity to negative feedback, while those with higher self-esteem cope more adaptively.

Cultural and Contextual Factors

The impact of feedback on stress and performance is also shaped by cultural norms and power dynamics. What constitutes “well-structured” feedback can differ across cultures – a direct critique might be motivating in one culture but seen as harsh and stress-inducing in another. For example, American managers often soften negative feedback with positive comments, aiming to protect the employee’s ego, whereas Dutch or German feedback culture is more blunt and straightforward. A style that is normal in one context can be misinterpreted as aggressive or demoralizing elsewhere. Similarly, feedback coming from a manager (high power) versus a peer has different stress implications: supervisor feedback carries formal consequences and may induce more acute stress, whereas peer feedback might feel less weighty but could be dismissed or misunderstood if not structured well. Studies in educational and corporate settings find that feedback from an expert or authority figure is often given more credence – for instance, teacher trainees rated instructor feedback as more helpful than peer feedback due to its specificity, clarity, and supportive tone. Nonetheless, creating a safe feedback environment is crucial in all contexts: employees (or students) need psychological safety to ensure feedback is taken as intended (a help, not a threat).

Implications

Effectively harnessing eustress via feedback requires thoughtful delivery and an understanding of employee differences. Organizations and leaders can train managers in constructive feedback techniques (specific, timely, respectful) to maximize positive stress. Encouraging a growth-oriented culture – where challenges and even failures are framed as learning opportunities – helps employees appraise feedback with a challenge mindset rather than a threat mindset. Additionally, attention to cultural sensitivities and individual coaching (e.g. building coping skills and resilience) can prevent feedback from crossing the line into distress. In sum, well-structured feedback is a powerful tool: when used properly, it propels employees into the optimal zone of stress for peak performance, fostering focus, innovation, and growth. If misused, however, feedback can induce harmful stress, so finding the “tipping point” between eustress and distress is key to sustained positive outcomes[3].

Introduction

Modern organizations increasingly recognize the value of effective performance feedback in driving employee development and productivity. Feedback – whether in formal performance reviews or informal coaching – provides individuals with information on their progress and areas for improvement. However, feedback is often a double-edged sword: while it can motivate and guide employees, it can also be a source of stress for the recipient. Traditionally, the term “stress” carries a negative connotation, but contemporary research differentiates between distress (debilitating stress) and eustress (beneficial, “good” stress). This report explores how well-structured feedback can tip the balance toward eustress, thereby enhancing rather than hindering employee performance.

Well-Structured Feedback is defined here as feedback that is clear, specific, timely, and contextualised. Rather than vague praise or ambiguous criticism, well-structured feedback pinpoints what exactly the employee did well or poorly, relates it to predefined goals/standards, and is delivered soon after the observed behavior. For example, telling an employee “Your last report was well-organized and the data analysis was thorough, but the conclusions section lacked two key recommendations we needed” is far more actionable (and thus less stress-inducing) than saying “Your report wasn’t good.” Key elements of effective feedback include:

- Clarity and Specificity: Employees should know exactly what aspect of their performance is being discussed and why it matters. Specific feedback tied to objective goals is more readily accepted and creates a clear path for improvement. In contrast, ambiguous feedback can create uncertainty – a known catalyst for stress. Clarity essentially transforms what might be a hindrance stressor (unclear expectations) into a challenge that can be tackled.

- Timeliness: Feedback is most effective when delivered promptly, while the memory of the behavior or task is fresh. Timely feedback allows employees to connect the information with their actions and adjust accordingly. If feedback is delayed excessively, it can lose relevance or come as a jarring surprise, potentially provoking anxiety (“Why didn’t I hear about this sooner?”). Studies in educational settings show that delayed feedback undermines motivation – for instance, university students reported significantly lower motivation when feedback on assignments was given more than 10 days later than when it was given promptly.

- Contextualisation: Feedback should be given with appropriate context – considering the employee’s role, the circumstances, and their experience level. Contextualising feedback means framing it as part of a developmental narrative (e.g., “Given your six months in the role, this level of detail is a great start; as you grow into the position, here’s how you can further improve...”). Context helps the recipient see feedback as fair and relevant, which reduces the likelihood of defensive or stress responses. It also means aligning feedback with growth-oriented contexts (“high-stakes or growth-oriented feedback environments” as in the user’s prompt) – for example, emphasizing that the feedback is intended to help the employee reach the next level or achieve their personal goals, not just to point out flaws.

- Constructive and Respectful Tone: While not explicitly listed in the prompt’s definition, the manner of delivery is implicitly crucial. Research and best practices indicate feedback should be delivered in a positive or at least neutral tone, focusing on behaviors rather than personal attributes. Even when giving corrective feedback, framing it as “areas for growth” or “how to improve” rather than as personal failings helps induce a sense of challenge (the employee sees a solvable problem) instead of threat (feeling attacked or hopeless). A respectful approach that acknowledges what was done well before what needs correction (often called the “feedback sandwich,” used judiciously) can cushion stress – though cultural norms vary, as we will explore.

When these elements are in place, feedback is more likely to be perceived by the employee as useful information rather than personal criticism. This perception is pivotal in determining whether the feedback causes eustress or distress. Eustress (a term combining “eu” = good + stress) was originally coined by Hans Selye to describe the positive adaptive stress that pushes organisms to perform better. In workplace terms, eustress is the energized feeling you get when facing a challenge that is within your abilities to conquer – it’s the “nervous excitement” before a big presentation or the focused rush when tackling an important project under a tight deadline. Physiologically, eustress and distress may feel similar (heart rate increases, adrenaline flows), but the psychological appraisal differs. If the situation is viewed as challenging-but-beneficial, the stress is eustress; if viewed as threatening or unmanageable, it’s distress.

Eustress, Distress, and the Stress–Performance Curve

Figure: The classic inverted-U curve illustrating the relationship between arousal (stress) and performance. Moderate stress yields optimal performance, whereas too little stress leads to under-performance and excessive stress causes performance to deteriorate[2].

It has long been recognized that not all stress is bad. In fact, a certain level of acute stress can be beneficial for performance. The Yerkes-Dodson law, first proposed in 1908, described an inverted-U relationship between arousal (which we can interpret as stress level) and performance[1]. At low levels of stress or pressure, individuals may feel under-stimulated or complacent, and performance suffers due to lack of focus or motivation. As stress increases to a moderate level, people become more alert and energized – this arousal can sharpen their attention and effort, often improving performance up to an optimal point[1]. However, beyond that tipping point, excessive stress overwhelms an individual’s capacities, leading to errors, cognitive overload, and performance deterioration. This inverted-U concept maps closely to the ideas of eustress and distress: the rising slope of the curve corresponds to eustress (good stress that enhances performance), and the descending slope represents distress (bad stress that impairs performance).

Eustress in the workplace is the kind of stress response that is short-term, exhilarating, and performance-enhancing. It often arises in challenging but rewarding situations, such as tackling a project that stretches one’s skills or receiving a constructive critique that sparks self-improvement. Physiologically, eustress might trigger the same “fight-or-flight” hormones as distress (you may get butterflies in your stomach, a racing heart, or a burst of adrenaline), but psychologically it is accompanied by positive emotions: excitement, satisfaction, heightened focus, and a sense of meaning or anticipation. One study using a multimodal stress measurement in workplaces found that moderate stress was associated with increased productivity and a more positive mood, whereas both low stress (boredom) and high stress (distress) were linked to lower productivity and negative mood. In other words, employees actually operate best with a healthy dose of stress – enough to energize them, but not so much as to cause distress.

In contrast, distress is the form of stress people typically fear: it is prolonged or extreme, and it triggers negative emotional states (anxiety, helplessness, anger) along with performance deficits. Distress occurs when challenges are perceived as overwhelming or unsolvable. For example, an employee who receives scathing, unconstructive criticism might feel threatened and inadequate – a response of distress that can derail their focus and confidence. The same workplace study mentioned above noted that when individuals experienced coexisting eustress and distress, the negative effects of distress tended to overpower the positive (i.e. the person’s mood and productivity took a downturn). This underscores that while some stress is good, strong negative stress can eclipse the benefits of any positive challenge. It’s therefore crucial to understand how to keep feedback-induced stress on the eustress side of the spectrum.

One way to distinguish eustress from distress is through the concept of stress appraisal – how an individual cognitively evaluates a stressor. Psychologist Richard Lazarus’s transactional theory of stress tells us that it’s not just the stressor itself, but how we perceive it (challenge vs. threat) that determines our response. If a demanding situation is appraised as a challenge (“I can handle this with effort, and it will help me grow”), the resulting stress is likely to be eustress. If the same situation is appraised as a threat (“This is too much; I will fail or be harmed”), the resulting stress is distress. This appraisal difference is evident in physiological responses too – eustress tends to come with approach-oriented responses (e.g., engaging with the task, problem-solving), whereas distress often triggers avoidance or panic.

In feedback scenarios, the goal is to have the recipient appraise the feedback as a constructive challenge rather than a personal threat. The structure and delivery of feedback play a pivotal role in shaping this appraisal. Before diving into individual differences, we will examine feedback itself as a potential stressor and how well-structured feedback can push employees into that optimal stress zone where performance is maximized.

Feedback as a Challenge Stressor: Turning Evaluation into Eustress

Feedback in the workplace can be considered a social stressor – being evaluated, even constructively, naturally elevates arousal and can trigger self-consciousness or concern. However, not all feedback causes the same stress reaction. We distinguish between:

- Feedback as a Challenge Stressor: These are feedback instances that, despite possibly pointing out shortcomings, are delivered in a way that the employee sees as achievable and fair. Challenge stressors are work demands that, while difficult, carry potential gains (learning or rewards) and thus can invoke eustress. A clear performance goal set by a manager or a tough but attainable target accompanied by actionable feedback are examples. Such feedback might sound like, “I’m giving you these critiques because I know you can improve and excel in the next project”, which frames the stressor (feedback) as an invitation to grow. Research in organizational psychology often contrasts challenge vs. hindrance stressors: challenge stressors (like time pressure or high responsibility) are typically associated with positive outcomes such as higher engagement and performance, whereas hindrance stressors (like red tape or role ambiguity) lead to negative outcomes[2]. Well-structured feedback, by virtue of providing clarity (reducing ambiguity) and focusing on improvement (a form of encouragement), converts what could be a hindrance into a challenge. There is empirical support for this: a meta-analysis found that challenge-type stressors have a positive relationship with job performance and motivation, in part because they increase positive affect and self-efficacy in employees[2]. In essence, good feedback can serve as a challenge stressor that energizes employees, aligning with eustress.

- Feedback as a Hindrance (or Threat) Stressor: This is feedback perceived as unjust, unhelpful, or indicating an insurmountable problem. Examples include feedback that is overly negative with no guidance, or vague statements like “You need to do better” without context – these create stress by heightening uncertainty or fear of failure. In such cases, feedback is a source of distress: it might demoralize the employee or make them anxious about their job security or social esteem. Physiologically, this threat response can spike cortisol levels and trigger defensive reactions. One study on performance feedback and stress found that negative performance feedback led to a “sensitized” cardiovascular response during subsequent stressful tasks, meaning the individuals stayed overly aroused and stressed, whereas positive feedback helped them adapt and dampen their stress response in later challenges. This indicates that when feedback is taken as a threat, it can have a lingering negative effect on the body’s stress regulation, keeping someone in a high-stress state that is detrimental to performance and health. In contrast, positive or well-delivered feedback seems to foster resilience – it can actually help people cope better with the next stressor by boosting their confidence (the study showed improved cardiovascular habituation after positive feedback).

The way feedback is framed and delivered can often determine which of the above categories it falls into. For instance, consider feedback given in a high-stakes context like an annual performance review:

- If the manager provides concrete examples of the employee’s behavior, aligns them with clear expectations, and expresses belief in the employee’s ability to improve (“You’ve handled client calls very well on average, though in two instances last quarter you struggled with technical questions. I suggest spending some time with our product team to deepen your knowledge – I’m confident you can become one of our go-to experts on this.”), the employee is likely to feel challenged but supported. The stress they feel walking out of that review is eustress – perhaps a heightened sense of urgency to learn, but also a reassurance that their boss believes in them. They might even feel motivated and excited to prove themselves. This state is linked to higher subsequent performance and engagement, as the employee channels the stress into improvement efforts.

- If the manager provides vague or purely critical feedback (“Your technical knowledge is weak and caused issues. You need to be better at this; otherwise…” with an implied threat of consequence, and no guidance), the employee is likely to feel threatened and discouraged. The stress here is distress – the employee may ruminate (“My boss thinks I’m bad at my job”), experience anxiety about their position, or become defensive rather than proactive. Such a state can impair their focus and willingness to take on challenges. In some cases, employees may disengage or show a decline in performance following harsh feedback, a pattern noted in feedback intervention theory research where feedback that threatens self-esteem causes withdrawal or performance decrements. Indeed, poorly delivered feedback can backfire, promoting bad feelings and defensiveness instead of improvement.

Crucially, whether feedback is a challenge or a threat also depends on the employee’s mindset and context, not just the manager’s intent. A well-intended piece of feedback can still be misperceived if the employee is, say, extremely insecure or if there’s low trust in the relationship. This is why fostering a positive feedback culture and relationship safety is important. Employees who feel safe with the person providing feedback (i.e., they trust that the feedback is meant to help, not harm) are far more likely to receive even negative comments as constructive. Without that foundation, even mildly critical feedback can “trigger alarm bells,” as author Erin Meyer notes: the brain’s amygdala (the fear center) can hijack the response, causing the person to react defensively or shut down. Thus, the best managers and mentors strive to deliver feedback in a way that engages the rational mind (seeing the feedback’s logic and benefit) while calming the emotional fears of the recipient.

Empirical research underscores the “double-edged sword” nature of feedback. A notable study (Li et al., 2024) on R&D employees examined negative supervisory feedback and how employees’ cognitive appraisals (challenge vs. threat) affected their creative performance. The findings were illuminating: when employees interpreted negative feedback as a challenge, they actually experienced a reduction in “prevention focus” (meaning they were less fixated on avoiding mistakes) and an increase in creativity – essentially, they took the feedback as a worthwhile problem to solve, freeing them to experiment and improve. By contrast, those who saw the same feedback as a threat doubled down on prevention-focused thinking (playing it safe, trying not to do anything wrong) and their creativity suffered. In simpler terms, if the feedback made them eustressfully energized, they innovated; if it made them distressed and cautious, they stagnated. This study highlights that feedback doesn’t uniformly enhance or impair performance – its effect depends on the psychological lens through which it’s viewed. Well-structured feedback aims to cultivate the challenge appraisal, nudging the employee towards eustress.

Another angle to consider is how well-structured feedback mitigates the potential stress of uncertainty. One of the most toxic forms of workplace stress is role ambiguity – not knowing what’s expected or how one is evaluated causes persistent anxiety and confusion. Quality feedback directly combats role ambiguity by providing information and clear expectations. In fact, HR analytics have shown that employees with high role clarity (often a result of regular, specific feedback and goal-setting) are significantly more efficient and effective than those with role ambiguity. Role clarity reduces unnecessary stress by eliminating the “guesswork” and worry about one’s standing, thus any stress that remains is more likely to be tied to meeting concrete challenges (eustress) rather than fretting over unknowns.

Finally, it’s worth noting that even positive feedback can be a form of eustress. When an employee is praised for good performance, it often raises the bar of expectation – which can create a challenge to maintain or further excel. Positive feedback typically boosts self-efficacy (one’s belief in their competence), which is a great buffer against distress, but it can still produce a mild arousal as the person feels, “Now I really need to keep it up!” That’s generally a healthy pressure, as long as it doesn’t slip into perfectionism anxiety. The study from University of Limerick (Brown & Creaven, 2017) cited earlier found that positive performance feedback helped participants adapt better to repeated stressors, essentially by increasing their confidence and calming their physiological stress responses. This suggests a reinforcing loop: good feedback (including praise) builds an employee’s resilience to future stress, meaning they’re more likely to handle challenges as eustress. Negative feedback, if not well managed, can do the opposite – sensitizing people to stress such that their alarm bells ring more intensely next time.

In summary, well-structured feedback acts as a positive catalyst. It turns the evaluation process into a manageable challenge and an opportunity for growth. By doing so, it generates eustress that can boost focus and performance. Poorly delivered or structured feedback, conversely, is often appraised as a threat, leading to distress and adverse outcomes. Next, we will delve into what happens to an employee under feedback-induced eustress: how does it impact their cognitive functioning, decision-making, and motivation on the job?

Impact on Cognitive Functions and Performance Outcomes

When an employee experiences eustress as a result of feedback, several noteworthy effects on cognition and performance can occur. Eustress can be thought of as the optimal activation state – the mind and body are stimulated but not overloaded. This state has distinct influences on attention, decision-making, creativity, and motivation, each of which we examine below. For contrast, we will also note what happens under distress in these areas. Table 1 summarizes the key differences in outcomes between eustress (challenge response) and distress (threat response) based on research findings:

| Aspect | Eustress / Challenge Response | Distress / Threat Response |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Reaction | Stimulating and manageable – triggers excitement, engagement, and optimism (often described as “nervous energy”). The individual feels challenged but confident (or at least capable) that they can meet the demand. | Overwhelming or fear-inducing – triggers anxiety, frustration, or a sense of dread. The individual feels threatened, possibly leading to panic or a sense of helplessness if they believe the situation exceeds their abilities. |

| Attentional Focus | Heightened focus on the task at hand. Moderate stress narrows attention to relevant cues, filtering out distractions. This can improve concentration and efficiency, as the person zeroes in on goals or problem-solving (often called “tunnel vision,” but in a useful sense). For example, an employee under eustress might be intensely “in the zone,” prioritizing key feedback points and working systematically on them. | Tunnel vision to the point of oversight. High stress causes extreme perceptual narrowing – important information can be missed because the person fixates on the stressor or a limited set of cues. Decision-making quality drops as they might ignore alternatives or long-term consequences in favor of immediate relief. For instance, an employee in distress from harsh feedback may obsess over one criticized detail and fail to see the bigger picture, or make hasty decisions just to escape the pressure. |

| Decision-Making & Creativity | Adaptive decision-making is often supported under eustress. The individual experiences enough arousal to think quickly and act, but not so much that they lose cognitive flexibility. They remain in a problem-solving mindset. Creative performance can flourish if the person sees the challenge positively – e.g., an employee might brainstorm innovative solutions to address feedback points when they’re excited by the challenge. Indeed, studies show that when negative feedback is appraised as a challenge, employees maintained lower prevention-focus and achieved higher creativity in their work. Eustress encourages taking initiative and calculated risks (since the person is motivated to overcome the challenge). | Impaired decision-making is common under distress. High anxiety can lead to cognitive overload or analysis paralysis, or conversely snap decisions that are not well thought-out. Research finds that stressed individuals often resort to simplistic or habitual choices, failing to consider all options, and can become rigid in thinking. Creativity tends to plummet because the person shifts to a prevention focus – they’re more concerned with avoiding mistakes than with innovating. For example, an employee who feels threatened by feedback might stick strictly to familiar methods and avoid experimentation, which in turn stifles learning and improvement. |

| Motivation & Mood | Generally elevates positive affect and motivation. A challenge perceived in a positive light often comes with emotions like enthusiasm, pride (e.g., “I’ll show I can do this”), and a sense of determination. Eustress can boost intrinsic motivation – the employee wants to meet the challenge for personal satisfaction and growth. The concept of “thriving under pressure” applies here; employees often report feeling invigorated by reasonable challenges and show higher engagement and commitment. (In one study, challenge stressors increased employees’ positive mood and self-efficacy, which led to better vitality and growth at work[2]) | Often deteriorates mood and motivation. Distress is accompanied by negative emotions (anger, fear, sadness) that can sap an individual’s drive. The experience is more about enduring than thriving. Employees under distress may become demotivated – feedback that feels like a personal attack can lead to disengagement or apathy (e.g., “Why bother trying if I’m just going to be torn down?”). In severe cases, distress from feedback can create a fear of taking on new challenges, leading to stagnation. Additionally, chronic distress is linked to burnout symptoms (exhaustion, cynicism). As a simple indicator: the presence of negative mood and low morale after feedback is a sign that the feedback induced distress rather than productive stress. |

Table 1: Comparison of outcomes under feedback-induced eustress vs. distress, based on various studies and theoretical insights.

It’s important to note that short-term eustress boosts (better focus, quick thinking) can translate into longer-term performance gains if experienced frequently in a supportive environment. For example, an employee who repeatedly receives well-structured feedback might frequently enter that optimal stress zone, leading over time to greater skill acquisition and confidence. This contributes to what researchers call thriving at work – a state of continuous learning and vitality. On the flip side, repeated episodes of distress from feedback can accumulate and lead to performance decline or turnover (employees may seek to escape an environment they find psychologically threatening).

Focus and Cognitive Load

One of the clearest immediate effects of acute stress is on attention. Under moderate stress (eustress), the brain tends to increase focus on task-relevant information, a phenomenon supported by Easterbrook’s (1959) cue-utilization theory. For instance, imagine an employee who just got feedback that their upcoming client presentation needs major improvements in the data section – and the presentation is tomorrow. The acute stress response will likely help them concentrate intensely on that data section for the rest of the day, ignoring less critical tasks or social media distractions. In this scenario, the stress (if kept at a non-panic level) acts as a focusing agent, which can improve the quality of work on the specific area of concern.

However, if stress crosses into distress, the degree of narrowing can become detrimental. The employee might become so fixated on one aspect (say, obsessively tweaking the data slides) that they neglect other important parts of the presentation, or they might lose the ability to think creatively about how to present the data and just overload the slides in a frantic attempt to cover every detail. Under high distress, working memory and complex processing suffer – the person might feel mentally “scattered” or unable to juggle multiple ideas, which is consistent with findings that people under extreme stress consider fewer alternatives and often revert to habitual or simplistic solutions.

It’s also been observed that stress can influence the filtering of information: under pressure, peripheral information (which might be irrelevant noise, but could also sometimes be useful context) is often filtered out. In eustress, this typically means one ignores distractions – a beneficial focus. In distress, though, the “tunnel vision” can exclude relevant inputs (e.g., ignoring colleagues’ suggestions or failing to notice new data) which can hurt decision quality. An optimal feedback scenario would therefore create enough urgency to focus the mind, but not so much threat that the person stops listening to input or exploring ideas.

Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

Decision-making under stress is a well-studied area, especially in high-pressure fields like aviation, emergency response, and the military. The findings from those domains also apply in principle to workplace feedback situations: moderate stress can improve speed of decision-making and even accuracy for straightforward tasks, but complex decisions requiring creativity and long-range planning degrade under high stress.

In a workplace context, consider problem-solving after feedback: Suppose a manager tells a team, “Our client wasn’t happy with the last project outcome; we need a radically better approach this time.” This feedback induces stress about finding a better solution. If taken as a motivating challenge, the team might enter a highly focused brainstorming mode, leveraging adrenaline to generate and evaluate ideas efficiently (perhaps working late with a sense of mission). They might feel a bit of pressure, but also a determination to succeed – leading to a well-thought-out plan (eustress driving effective problem-solving). If instead the team is gripped by fear of blame (distress), their decision-making might suffer – they could rush into a safe but mediocre plan just to have an answer (a knee-jerk reaction), or they might overanalyze and delay out of fear of more criticism (paralysis). Stress research indicates that perceived threat can indeed cause decision-makers to narrow their options and sometimes choose more risk-averse actions, even if those aren’t optimal (for example, sticking to a familiar approach that they know is not great but feels “safer” than proposing a novel idea that might get shot down).

Interestingly, one study in a clinical performance review context (cited in a review of acute stress on performance) showed that individuals under acute stress tend to revert to well-learned behaviors and their decision strategy simplifies. If their training is good, this can be fine; if not, it can lead to mistakes. In an organizational learning sense, this implies: if we want employees to handle feedback-induced stress well, we should also train and equip them with good problem-solving habits and frameworks so that their “fallback” under stress is still effective.

Creativity and Innovation

The relationship between stress and creativity is complex. A little stress can indeed spark creativity – the urgency and focus can push people to think differently. Some creative individuals even seek mild stress or tight deadlines because it “forces the muse.” The R&D employee study (Li et al., 2024) we discussed earlier provides empirical backing: those who received negative feedback and appraised it as a challenge actually became more creative, as the pressure motivated them to find novel solutions and they weren’t inhibited by fear of failure. This aligns with the idea of eustress unlocking creative energy. When you’re eustressfully engaged, you often experience a state of flow or deep engagement, which is conducive to creative thought.

On the contrary, severe stress or a threat state is usually bad for creativity. Fear and creativity do not mix well – anxiety tends to make thinking more rigid and limited. The same study showed that employees who reacted to feedback with threat appraisal became more prevention-focused and less creative. In general, if an employee is worried about being judged or punished, they’ll be less likely to put forward wild, creative ideas; they’ll play it safe.

Thus, for innovation-driven workplaces, it’s crucial that feedback creates a sense of challenge without fear. Some companies achieve this by explicitly encouraging experimentation and framing failures as learning opportunities. In such cultures, when feedback identifies a mistake or failure, employees may feel pressure to come back with a creative solution (good stress) but not worry that their job is on the line (fear). This balance can be delicate, but it is exactly what differentiates high-performing innovative teams – they have high standards and candid feedback (intense in a way that drives eustress), yet psychological safety that blunts distress.

Motivation and Engagement

Motivation is often the bridge between the internal state of stress and the outward behavior of performance. Eustress typically correlates with approach motivation – the person is motivated to move toward a goal or reward. Distress correlates with avoidance motivation – the person is motivated to move away from a threat or pain. Well-structured feedback is aimed at cultivating approach motivation: it points to a positive outcome (improvement, achievement) that the employee can attain by addressing the feedback. This taps into intrinsic motivation by satisfying some core psychological needs: a clear path to mastery (competence), a sense that the person is trusted to act (autonomy), and often the feeling of being supported by the feedback-giver (relatedness). These align with Self-Determination Theory’s drivers of motivation.

Empirical evidence shows that when feedback is done right, it boosts engagement. A Gallup report, for instance, found that employees who receive meaningful feedback (especially frequent, strengths-focused feedback) are much more engaged in their jobs than those who don’t. Part of the reason is that good feedback creates that energizing eustress – employees have clear goals to strive for and a sense of progress, which is motivating. Even in the short term, as mentioned earlier, positive stress elevates mood and optimism, which are linked to willingness to exert effort and persist at tasks. Challenge stress tends to come with a sense of reward contingency (“if I rise to this challenge, I will achieve X”), which fuels motivation.

On the other hand, feedback-induced distress can undermine motivation severely. For one, distress often brings a negative mood, which colors one’s outlook and can lead to disengagement or learned helplessness (“nothing I do is good enough”). Additionally, if feedback is seen as purely punitive, employees might only be motivated to avoid further criticism, which leads to minimal compliance behavior rather than proactive engagement. They might also avoid seeking feedback in the future or even avoid challenging tasks entirely, hurting their growth. In educational psychology, studies have observed that students who receive harsh, unsupportive feedback can lose their intrinsic motivation to learn the subject; they start working only to avoid failure, not to excel. In the workplace, similarly, a employee constantly under distress from feedback might say, “I just keep my head down and try not to get noticed,” which is obviously not ideal for performance or career development.

In summary, feedback that creates eustress tends to invigorate employees – sharpening their focus, spurring effective decisions, fostering creativity, and boosting motivation – all of which contribute to improved performance outcomes. Feedback that creates distress does the opposite – it scatters attention, clouds judgment, stifles innovation, and saps motivation, thereby harming performance. The next logical question is: what determines whether a given employee falls into eustress or distress when receiving feedback? We’ve touched on the role of appraisal, but that appraisal is shaped by the person’s characteristics and environment. Let us explore the individual differences and contextual factors that mediate this relationship.

Individual Differences: Why Some Employees Thrive on Feedback Stress and Others Crumble

Not everyone reacts to the same feedback in the same way. Two employees could receive identical comments – one emerges energized and the other deflated. This variation comes down to individual differences in personality, mindset, and coping strategies, as well as past experiences. Recognizing these differences is crucial for managers and HR professionals, because it suggests a need to tailor feedback approaches or provide support based on individual needs.

1. Mindset and Stress Appraisal: Perhaps the most influential factor identified in recent research is whether an individual has a growth mindset and what researchers call a “stress-is-enhancing” mindset. These concepts are closely related. A growth mindset, as defined by Carol Dweck, is the belief that abilities and intelligence can be developed through effort, feedback, and learning. A fixed mindset is the belief that abilities are static and criticism is a judgment of one’s inherent ability. An employee with a growth mindset will interpret critical feedback as useful information to grow, even if it stings, whereas a fixed-mindset individual might interpret it as a statement about their personal worth or talent. Growth mindset employees tend to embrace challenges, persist in the face of setbacks, and learn from feedback[3]. In fact, research has shown they often seek out feedback in challenging situations as a strategy to improve[3]. This predisposition means they are primed to experience feedback as eustress – it aligns with their internal narrative that effort leads to improvement.

Closely related is the stress mindset concept (Crum et al., 2013). A “stress-is-enhancing” mindset is when a person believes stress can be beneficial and lead to gains in performance or health, whereas “stress-is-debilitating” mindset is the belief that stress is uniformly harmful. Studies indicate that people with a stress-is-enhancing mindset react to stressors with more positive affect and see stressful situations more as challenges than threats[3]. Feedback is a textbook case of a stressor where mindset matters. If I believe “a bit of stress will sharpen me and make me better,” I’m likely to take a tough performance review in stride and use it constructively. If I believe “stress will wreck me,” I’m more likely to be overwhelmed by the same review. In support of this, a hypothesis confirmed in Moyo (2025) was that employees with a high growth mindset appraise work stressors as eustress, whereas those with low growth mindset (fixed mindset) appraise them as distress[3]. In other words, mindset moderates the relationship between the feedback (stressor) and the type of stress outcome[3].

What’s promising is that mindsets can be changed or coached over time. Some companies incorporate growth mindset training or stress management interventions to help employees reinterpret stress. By encouraging a growth mindset culture (“We grow from feedback here”), organizations can shift more employees into seeing feedback stressors positively.

2. Personality Traits: Certain stable traits influence stress responses. For example, Neuroticism (the tendency to experience negative emotions easily) often correlates with perceiving events as more threatening and feeling distress. A highly neurotic person might react to mild criticism with outsized anxiety or defensiveness, whereas a person low in neuroticism (emotionally stable) might brush it off or lightly address it. Openness to Experience could play a role too – more open individuals might be curious about feedback and experiment with changes (lower distress), while less open folks might resist new ideas and feel stressed by feedback asking them to change their routine. Conscientiousness might go either way: conscientious employees often take feedback very seriously (which can cause stress), but because they are achievement-oriented, they may channel that stress into improvement (potential eustress). However, if extremely conscientious individuals tie their self-worth to performance, negative feedback could hit them hard (distress); balance is key.

There’s also the Type A vs Type B personality consideration. Type A individuals (competitive, urgency-driven) might actually thrive on feedback challenges – they treat it like a game to win, invoking eustress – but they’re also prone to stress-related strain if not managed. Type B (more relaxed) individuals might handle negative feedback calmly but also may not be as aroused to act on it (lack of any stress could mean lack of spur to improve).

Another relevant trait is self-esteem. Research has found that self-esteem levels influence how people respond to performance feedback. The earlier cited study by Hughes (2007) and Brown & Creaven (2017) noted that higher self-esteem individuals showed less extreme cardiovascular reactions to stress and adapted better after receiving feedback. Those with low self-esteem might interpret negative feedback as confirmation of their inadequacy, leading to a spiral of distress and poor performance. High self-esteem can buffer some of the blow – such individuals may be more likely to consider the feedback constructively or attribute negative feedback to fixable behaviors rather than global self-failure.

3. Coping Strategies: People have different default ways of coping with stress, and these can significantly affect outcomes of feedback. Two broad coping styles are problem-focused (or approach) coping and avoidance (or emotion-focused) coping.

- An employee with problem-focused coping will respond to stressful feedback by actively trying to solve the underlying issues. For example, if told their presentation skills are lacking, they might enroll in a public speaking workshop or seek advice – concrete steps to address the feedback. This approach is conducive to eustress because it treats the feedback as a problem to be solved, aligning with challenge appraisal. These employees often exhibit resilience; they might even “savor” challenges – one study mentioned savoring as the process of embracing positive aspects of stress, which was associated with eustress and engagement[3]. They derive a sense of accomplishment from tackling difficult feedback points, which further reinforces the positive cycle.

- An employee with avoidant coping will respond to feedback-induced stress by avoiding or denying the issue. They might procrastinate on making changes, downplay the feedback (“Oh, it’s not that important”), or avoid seeking further feedback. Avoidant coping is generally linked to worse outcomes – it might reduce stress in the very short term (by not thinking about the issue), but the underlying problems fester, and the person likely feels ongoing distress subconsciously. In the context of feedback, avoidance could mean the employee doesn’t improve (performance stagnates or worsens, leading to more negative feedback later, a vicious cycle). Research has consistently found that avoidant coping is associated with greater psychological distress and poorer adjustment[3]. In a workplace example, an employee who copes with a tough review by withdrawing (perhaps calling in sick the next day, or avoiding projects where they might be evaluated) is on a trajectory of distress and declining performance.

One extreme form of avoidance in organizations is feedback avoidance behavior – deliberately not asking for feedback or even rejecting opportunities to get evaluated. This often stems from fear of negative results. While it might shield one’s ego temporarily, it also removes the opportunity for positive stress and growth, usually leading to career stagnation. A recent study (Wang et al., 2020, in J. of Managerial Psychology) indicated that employees under abusive supervisors resorted to feedback avoidance as a coping mechanism, which alleviated some emotional exhaustion in the short run but had complex effects on their engagement. Essentially, if employees feel feedback is “unsafe,” they’ll avoid it, which speaks to the importance of having supportive management so that employees use approach coping (addressing feedback) instead of avoidance.

4. Past Experiences and Self-Efficacy: An often overlooked factor is the individual’s history with stress and feedback. If someone has repeatedly experienced that taking on challenges leads to success, they develop high self-efficacy and a trust in the process. They might recall, “Last time I got tough feedback, I worked hard and turned it into a win; I can do it again.” This mastery experience gives them confidence and tends to make new feedback-induced stress feel more like eustress (because they expect a positive outcome). On the other hand, individuals who have a history of failures or harsh feedback with no wins may approach new feedback with a sense of defeat, basically bracing for distress.

In educational psychology, this relates to learned helplessness vs mastery orientation. A person who hasn’t seen the link between effort and improvement might respond to feedback with helplessness (“nothing I do will change this”), which is distressing. In contrast, someone with a mastery orientation thinks effort will pay off, turning feedback into a challenge.

5. Emotional Intelligence: This can also play a role. An employee with high emotional intelligence (EI) may better regulate the initial pang of stress from criticism and not let it overwhelm them. They might interpret the feedback more rationally and seek clarification rather than ruminate emotionally. Such regulation can prevent the slide into distress. They’re also likely to communicate better with the feedback giver (asking questions, showing appreciation for feedback), which can turn a stressful encounter into a constructive dialogue – again, shaping the appraisal toward challenge. Employees lower in EI might take feedback very personally and struggle to manage the emotions it evokes, increasing the chance of a threat appraisal and defensive reaction.

6. Personal Life Stress and Resources: Finally, it’s worth noting that an employee’s general stress level and resources will influence how they take on additional stress from feedback. Someone who is already extremely stressed (due to personal issues or overwork) has less capacity to absorb even a well-structured critique; they might tip into distress simply because their bucket is full. Conversely, someone who is well-rested, supported, and otherwise stress-free might handle even relatively harsh feedback with composure. This ties into the notion of stress tolerance – which can be built up, but varies from person to person.

In practice, what do these differences mean? For managers and consultants, it means feedback should not be one-size-fits-all. Tailoring feedback strategy to the individual can make a big difference. A few examples: - With a growth-minded, resilient employee, one can be more direct and stretch them – they’ll likely rise to it and enjoy the challenge (they might even prefer you don’t sugarcoat it). These folks benefit from being pointed to higher goals. - With a more sensitive or defensive employee, one might need to be more gentle, building up their belief in improvement. Framing feedback in a more positive light (“I believe you can get there, let’s work on these specifics…”) and checking their understanding can prevent them from feeling threatened. It might also help to limit the amount of critical feedback given at once for such individuals, to avoid overload. - Encouraging employees to develop coping skills is also part of the solution. For instance, if someone tends to catastrophize, coaching them in reframing techniques (like considering feedback as specific to a situation, not a universal statement of their ability) can shift their mindset over time. - Additionally, fostering peer support and mentorship can help. Sometimes if an employee sees colleagues positively handling feedback, it models the behavior (social learning). Peer discussions can normalize that “we all get tough feedback, it’s how we improve,” which buttresses a growth mindset culture.

In sum, individual differences act as a lens that can either magnify a stressor into distress or filter it into eustress. Understanding those lenses – and helping to adjust them where needed – is key to ensuring feedback has its intended, positive effect.

Cultural and Contextual Considerations: Feedback Across Environments

Feedback and stress do not occur in a vacuum. The context – organizational culture, national culture, and the relationship between the feedback giver and receiver – can strongly influence whether feedback is experienced as eustress or distress.

1. Organizational Culture and Psychological Safety: Some organizations have a culture of open, continuous feedback (think of agile tech companies with regular retrospectives), while others have infrequent, formal reviews. In companies where feedback is frequent, normalized, and two-way, employees might be less startled by any single instance of feedback – they expect it, perhaps even welcome it as part of work life, which can reduce the threat response. Moreover, if leadership models learning from feedback openly (for example, leaders admitting mistakes and showing how they improved), it reinforces that feedback is a tool for growth, not just a performance verdict. This kind of culture likely produces more eustress responses.

A critical component here is psychological safety – the shared belief that it’s safe to take interpersonal risks (like speaking up, asking questions, or admitting errors) in the workplace. High psychological safety means an employee is less likely to fear that negative feedback will lead to humiliation or punishment; instead, they trust it’s meant to help. Studies have found that teams with high psychological safety respond to mistakes or feedback by learning and adapting (challenge response), whereas teams with low safety often respond by covering up or blaming (threat response). Google’s internal research (Project Aristotle) famously identified psychological safety as the number one factor in team effectiveness. Thus, contextualizing feedback as supportive and ensuring that employees don’t fear retribution for shortcomings will encourage eustress reactions.

2. Power Dynamics – Manager vs Peer Feedback: The source of feedback significantly colors its reception. Generally, feedback from a manager or someone higher in the hierarchy carries more weight and, inherently, more potential threat because that person often has power over promotions, raises, or job security. For example, a pointed critique from one’s boss might spike adrenaline and concern (“Uh oh, my job or reputation is on the line”), whereas the same critique from a peer might sting but not invoke fear of formal consequences. Therefore, managerial feedback can induce stronger stress responses. But whether that is eustress or distress depends largely on how the manager uses that power. A good manager-employee relationship – one with trust and mutual respect – can make even tough feedback feel motivating (“I don’t want to let my boss down; they believe I can improve”). A toxic relationship or an abusive boss can make even mild feedback feel like an attack, with all the hallmarks of distress (fear, anger, desire to retaliate or withdraw). Unfortunately, research on abusive supervision shows it increases subordinates’ stress and often leads to feedback avoidance and lower performance over time. This underscores the importance of manager training in feedback delivery as well as simply treating employees with respect.

Peer feedback, on the other hand, is interesting because peers are equals – their feedback may be taken more or less seriously depending on the culture. In collaborative cultures, peer feedback is a valuable supplement to managerial feedback and can be less intimidating. Peers might give advice in a more casual, relatable way, potentially causing less defensive reaction. However, peer feedback comes with its own challenges: without authority, peers might sugarcoat or avoid giving honest feedback (limiting its usefulness), or if they do give strong feedback, it could be interpreted as overstepping or personal criticism if not done carefully. The teacher education study we encountered showed that novices rated instructor (authority) feedback as more beneficial than peer feedback, partly because instructors provided more specificity, expertise, and support – whereas peer comments, unless trained, might lack clarity or be taken with skepticism. This implies that for peer feedback to induce eustress and improvement, it should be structured and trained as well. When peers are trained to give specific, constructive feedback, and when a culture of collegial support exists, peer feedback can be a powerful, less formal way to continuously improve (with possibly lower stress, since there’s no formal evaluation attached). But if peer feedback is unsolicited or delivered insensitively, it might trigger interpersonal conflict stress.

3. Cross-Cultural Differences: On a national or ethnic culture level, norms about giving and receiving feedback vary widely, which affects stress responses. Erin Meyer’s cross-cultural management research provides vivid examples. In some cultures, such as the Netherlands, Germany, or Israel, communication is very direct and negative feedback is given bluntly, with the assumption that adults can take criticism straightforwardly and it’s more respectful to be honest. Employees raised in those cultures might have a higher tolerance for direct criticism – they might experience a blunt feedback as clear and honest (potentially eustress if they see it as a challenge to fix), rather than as a personal attack. On the flip side, cultures like the US or many East Asian countries (Japan, many parts of China, Indonesia, etc.) often practice more indirect feedback, wrapping negative points in praise or stating them in subtle ways to preserve “face” and harmony. An employee from such a culture might be accustomed to reading between the lines. If they then receive feedback in a blunt manner (say, an American employee getting feedback from a Dutch manager like “This report is simply not good, you must change X and Y”), they might find it unusually harsh and demoralizing – a potential distress response because it violates their expectations of cushioning. Conversely, a Dutch or Russian employee might find the typical American managerial feedback style (lots of positives around a core critique) to be confusing or even insincere, possibly stressing them out because they’re not sure what the real message is. They might prefer directness as it gives clarity (reducing uncertainty stress).

One humorous but instructive anecdote: A French employee once described Americans as “big babies” in how feedback must be given – needing lots of positivity and encouragement – whereas Americans often perceive French or Dutch feedback as needlessly harsh. Neither is inherently right or wrong; it’s about what people are used to and interpret correctly. The stress comes from the mismatch of expectations. As Meyer noted, “A direct approach that’s welcomed at home can be easily misinterpreted as aggressive elsewhere.”.

Therefore, in global teams, managers should be aware of these cultural preferences. When providing feedback to someone from a different cultural background, it’s wise to adjust the style or at least preface how you will give feedback to avoid misinterpretation. For example, managers can explicitly say, “I tend to be direct because I want to give you clear guidance – please know my intent is to help, not to offend,” which can help mitigate a threat reaction across a cultural divide.

Another cultural aspect is power distance (how much a culture expects hierarchy). In high power-distance cultures (many Asian, African, Latin American cultures), criticism from a boss can be extremely stressful because of the deference and stakes involved – subordinates may not even feel allowed to speak up or explain themselves, potentially intensifying a sense of helplessness. In such cultures, managers often soft-pedal direct criticism or deliver it through indirect means to avoid shaming the subordinate publicly. In low power-distance cultures (like Northern Europe, Australia), more open dialogue is expected and an employee might freely debate or clarify feedback with their boss, which can actually reduce stress through conversation.

4. Educational Context Parallels: While this report focuses on professional work settings, many principles carry over from educational research (after all, students “perform” in academics and receive feedback from teachers). In education, timely and specific formative feedback is known to improve learning outcomes and student motivation. Students, like employees, experience stress around evaluations (tests, grades, critique on assignments). Studies have shown that framing academic challenges as opportunities to learn (rather than high-stakes judgments) encourages a challenge mindset, leading to better performance and persistence. For instance, an educational psychology review by Shute (2008) highlighted that directive feedback (explicit guidance on errors) helps learning more immediately than just broad comments, but it should be balanced to not stifle the student’s own problem-solving. If feedback is too vague or delayed, students often experience frustration or disengagement.

One relevant finding from higher education: a study found that students were significantly less motivated when feedback was given too late (more than 10 days) because by then the stress had either dissipated into apathy or turned to frustration at the lack of input. In contrast, prompt feedback kept them on their toes (productive stress to act while the material was still fresh). Another study on feedback specificity suggests that while high specificity helps initial performance, there is a nuance: too-specific feedback can sometimes limit exploration (people do exactly what the feedback says and no more). This is a note of caution – in the workplace, if we hand-hold too much in feedback, we might reduce the employee’s opportunity to find their own improved methods (possibly reducing creative effort or long-term adaptability). So, the context of learning stage matters: novices might need very specific guidance (to avoid distress of not knowing how to improve at all), whereas experts might benefit from a bit more open-ended feedback that still challenges them but lets them figure out the solution (to generate some creative eustress).

5. Philosophical Perspective on Stress and Growth: Stepping back, there’s a philosophical notion that adversity (within reason) is necessary for development – encapsulated in sayings like “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” (Nietzsche) or the Stoic idea of turning obstacles into fuel for progress. While those are not scientific claims per se, modern positive psychology has echoed similar sentiments in concepts like post-traumatic growth (growing stronger after overcoming challenges) and antifragility (systems that grow stronger when stressed, a term by Nassim Taleb). Well-structured feedback could be seen as a designed micro-adversity: a dose of challenge to stimulate growth. Too much adversity (abusive environment) breaks people (distress) – that’s not antifragile, it’s just destructive. But the right amount, delivered in a way that the person can absorb and learn from, can make them more resilient and capable over time. This aligns philosophically with a growth-oriented life stance: embracing challenges (and the stress that comes with them) as a path to excellence. Indeed, researchers Nelson & Simmons (2003) referred to eustress in terms of “strengthening” – employees experiencing eustress often report feeling more engaged and committed, as if they are reinforced by the experience of overcoming the challenge[3].

Cross-culturally, some have pointed out that Eastern philosophies like Buddhism treat stress (dukkha, suffering) as something to be mindful of and mitigated, whereas Western philosophies have often emphasized conquering challenges. In practice, workplaces worldwide now borrow from both: encouraging mindfulness and well-being (to manage distress) while also using stretch goals and “big, hairy, audacious goals” to challenge people (and create eustress). The key is balance and context – understanding the human element in all of this.

Finally, let’s consider high-stakes environments like medical, military, or emergency services (outside typical corporate, but instructive). In those fields, feedback can be literally life-saving (e.g., debriefing after a surgery or mission to improve). Individuals in those professions often undergo stress inoculation training – they’re repeatedly placed in challenging scenarios so that they learn to operate under stress without falling apart. As a result, they develop a sort of stress resilience and tend to interpret operational feedback in a very matter-of-fact way (e.g., a surgeon being told in a morbidity & mortality meeting that they made an error – it’s taken seriously but as part of the process to do better next time, not as a personal indictment). Such cultures treat feedback as an inherent part of mastery, which is an ethos corporate environments might aspire to on a psychological level.

To wrap this section up, context matters tremendously. The same feedback sentence said in two different companies – one supportive, one toxic – can have opposite effects on an employee. The same comment from a boss versus a peer, or in New York versus Tokyo, can land differently. Therefore, those providing feedback must be culturally intelligent and situationally aware. For global organizations, it may even be useful to have discussions on feedback norms – for example, teaching more direct cultures to add a bit of positive buffer when dealing with those from indirect cultures, and coaching indirect-culture employees not to read excessive negativity into direct feedback from certain colleagues. When context is handled well, it maximizes the chance that feedback will induce the intended eustress and performance boost rather than unintended distress.

Discussion and Conclusion

Integrating the Insights: The evidence compiled in this report paints a coherent picture: well-structured feedback can act as a positive form of stress (eustress) that enhances employee performance, but its success depends on thoughtful execution and individual and cultural factors. We find that clarity, specificity, timeliness, and supportiveness in feedback delivery are not just “nice-to-haves” – they are critical design elements that determine whether feedback will be a catalyst for growth or a trigger for fear. Feedback, in essence, is a powerful social interaction that can switch on an employee’s best self or worst anxieties.

When feedback achieves the right balance, it exemplifies the concept of challenge stressors benefiting organizations: employees receive a clear challenge, experience a manageable spike in stress that focuses their efforts, and respond with increased engagement, learning, and performance. This is reflected in outcomes like improved goal attainment, creative solutions, higher productivity, and personal development. Multiple studies, from meta-analyses in organizational behavior to controlled experiments in psychology, converge on the finding that moderate levels of stress linked to meaningful goals improve outcomes[2], whereas unconstructive or excessive stress harms them.

One might ask: How acute should this “positive stress” be? The idea of a tipping point between eustress and distress emerged in our exploration (notably from Moyo’s 2025 dissertation)[3]. It suggests there is a threshold of intensity and perhaps frequency beyond which even well-intended challenges become counterproductive. For example, giving tough feedback on every minor issue, every single day, might accumulate and tip employees into a chronic stress state. Thus, managers should calibrate not only how they give feedback, but how often and on what issues, prioritizing what’s most developmental. The goal is to keep employees in the productive zone of the stress curve as much as possible, with allowances for recovery and celebration of improvements to avoid burnout.

Implications for Practice: For HR professionals, corporate leaders, and consultants, these findings highlight several practical steps: - Train Feedback-Givers: Invest in training managers (and peer leaders) in effective feedback techniques. This includes coaching them to use specific examples, focus on behavior (not traits), and frame improvements in a positive light. It also means training them to read the employee – noticing signs of distress (e.g., visible anxiety or shutdown) and adjusting their approach (maybe slowing down, expressing support) in real-time. As part of this, cultivating empathy in managers will help them gauge how feedback is landing and manage the emotional side of the exchange. - Promote a Growth Mindset Culture: Organizations can incorporate growth mindset principles in their messaging and processes. This can range from including a blurb in performance evaluations that “Feedback is aimed at helping you grow, and effort/improvement is valued,” to workshops or internal communications that share stories of improvement. Leadership should model vulnerability by acknowledging their own learning processes. By reinforcing that talents are developed, not fixed, employees are more likely to take feedback as an opportunity (eustress) rather than a verdict (distress)[3]. - Ensure Psychological Safety: Create an environment where employees feel safe to fail and fix mistakes. This involves how managers react when things go wrong – if the first response is punitive, employees will fear feedback. If the first response is, “Okay, let’s understand what happened and how to improve,” employees will remain in problem-solving mode. Encouraging team norms like “We critique ideas, not people” and having regular debriefs normalizes feedback. Some companies institute “best failure” awards or have leaders share their own past failures and learnings, symbolically showing that learning trumps blame. When safety is present, feedback is less likely to be seen as a personal threat. - Customization and Dialogue: Adopting a feedback approach that allows dialogue can transform a stressful monologue into a coaching conversation. For instance, instead of a manager just saying what was wrong, they might ask the employee, “How did you feel that project went? Where do you see room for improvement?” This engages the employee’s own evaluative skills and may surface self-critique that the manager can then guide. It also gives the employee a sense of control and partnership in the process, which reduces feelings of helplessness or unfairness (key drivers of distress). In essence, coaching-style feedback (collaborative) tends to be less stress-inducing than judgment-style feedback (one-way). - Monitor Workload and Feedback Load: An often overlooked aspect is that if an employee is overwhelmed with work (high job demands) and at the same time receives a slew of developmental feedback, the combination can overshoot the eustress sweet spot. There’s only so much challenge one can take at once. So, HR and managers should be mindful of timing – delivering critical feedback during an already extremely stressful period (say, a company merger or a personal life crisis for the employee) might backfire. Whenever possible, significant feedback should come at a time (or be framed in a way) that the employee has the bandwidth to address it constructively. Aligning feedback with support (like offering resources, training, or extra time to work on the feedback areas) also ensures the stress is accompanied by a solution path. - Cross-Cultural Training: For global organizations, providing training or guidelines on cross-cultural feedback differences can prevent misunderstandings. Something as simple as making teams aware of Meyer’s culture map for feedback (which plots countries on direct vs indirect negative feedback scales) could be eye-opening. Teams can then establish a hybrid style that respects cultural preferences of members. For example, a multicultural team might agree on a signal phrase like “To be very direct…” before giving a blunt critique, to telegraph intent. Or adopt the practice of written follow-ups: in some cultures writing feedback (even if direct) is easier to accept than spoken face-to-face confrontation. Culturally savvy feedback reduces the chance of inadvertent distress. - Encourage Feedback Seeking and Reflection: Encouraging employees to actively seek feedback can also be beneficial. When an employee asks for feedback, they psychologically set themselves up to view it more as helpful (since they requested it) rather than feeling ambushed. Over time, this builds feedback resilience. Some companies include “actively seeks feedback” as a competency in reviews to nudge this behavior. Additionally, teaching reflection techniques (journaling about feedback, making action plans) helps employees process feedback on their own terms, again shifting control to them and framing it as a positive challenge they are managing.

Conclusion: In conclusion, well-structured feedback is akin to a well-calibrated dose of stress – much like a vaccine that challenges the immune system just enough to build strength, or a weight that muscles must strain against to grow stronger. Clarity, specificity, and timeliness in feedback provide the structure that makes the stressor clear and bounded, preventing the corrosive stress of uncertainty or perceived unfairness. When employees understand exactly what is expected and believe they can take action to improve, feedback becomes empowering. Under those conditions, the stress they feel can ignite focus, learning, and high performance – the very definition of eustress in action, where stress is not only not harmful, but is actually performance-enhancing.

We have also seen the nuances that this process is not automatic; the individual’s mindset and environment determine whether the spark of stress lights a productive fire or explodes unpredictably. Thus, organizations should view feedback not just as a managerial duty, but as a strategic lever to modulate employee stress and drive development. By creating a culture that values constructive feedback (and training people to give and receive it effectively), organizations tap into the motivational power of eustress. Employees then come to see feedback moments not with dread, but with a bit of excited anticipation – “What will I learn next, and how will it help me excel?”

Done correctly, feedback conversations become less about evaluation anxiety and more about joint problem-solving. Employees step away from such conversations challenged, yes, but also confident in a plan to meet the challenge. The acute stress from a frank critique or a high expectation transforms into fuel for focus and improvement, rather than a toxin of fear. And on the organizational level, this means a workforce that is continually adapting and elevating its performance, turning feedback from a source of tension into a cornerstone of a resilient, high-performing culture.

Ultimately, the interplay of well-structured feedback, eustress, and performance demonstrates a hopeful message: stress in the right form and dose is not the enemy of performance, but a necessary ally. By mastering the art of feedback – understanding its psychology and dynamics – leaders can induce the kind of stress that energizes growth, while minimizing the kind that hinders it. In a world where change is constant and improvement is the goal, harnessing eustress through effective feedback might just be one of the most important competencies for organizations and individuals alike.

Citations:

[1] Stress and Performance: A Review of the Literature and Its Applicability to the Military

[2] The Impact of Challenge and Hindrance Stressors on Thriving at Work Double Mediation Based on Affect and Motivation

[3] The Tipping Point between Eustress and Psychological Distress at Work: Effects of Occupational Stress on Employee Performance Outcomes